MRIT, MPL Consent Form

Save time during your next appointment! Complete your required forms online from any device at any time before your scheduled appointment.

“Bringing specialized veterinary surgical services to you!”

Jacqueline J Mair

DVM,MBA, Diplomate ACVS

SCHEDULE TODAY!

MRIT, MPL Information

The cranial cruciate ligament is the primary stabilizer of the canine knee. This ligament prevents cranial translation of the tibia and internal rotation of the tibia. Dogs undergo degeneration of their ligament (mucinous degeneration) for reasons we do not understand. This degeneration leads to rupture or tearing of the ligament. Less important stabilizers of the knee are C-shaped cartilage structures called menisci. Once the cranial cruciate ligament is torn, the medial meniscus is damaged over time by the abnormal motion of cranial translation of the tibia or drawer.

The cranial cruciate ligament has two major bands, a caudolateral band and a craniomedial band. Dogs can tear one or both bands. Once the ligament is torn, it will not heal. Many dogs may also have a torn medial meniscus dependent on the length of the injury. Again if the meniscus is torn, it will not heal.

Over time, in an attempt to stabilize the knee, dogs will develop what we refer to as medial buttress. This is an accumulation of fibrous tissue on the inside aspect of the knee. It spans the joint in an attempt to stop abnormal motion. Unfortunately, because this fibrous tissue is continuously stretched, it cannot adequately stabilize a knee.

Once the cranial cruciate has torn, this abnormality will lead to the development of arthritis. While we cannot stop arthritis from forming secondary to these joint abnormalities, we can stop the painful aspect of this injury with an extracapsular stabilization procedure.

The surgery we perform to stabilize the knee involves joint exploration where the remaining cruciate ligament is excised, and both the menisci are evaluated. If the medial meniscus is intact, we perform a meniscal release to try and eliminate future impingement and tearing. If the medial meniscus is torn, we remove it as it contains pain fibers and is an ongoing source of pain.

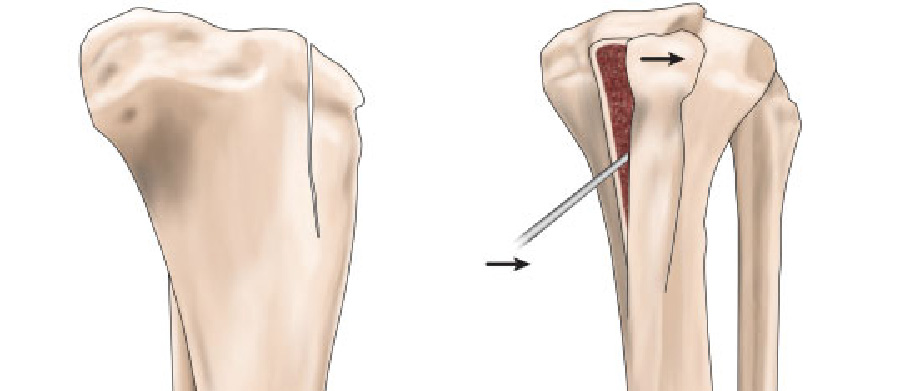

The next portion of the procedure is extracapsular stabilization. We place a heavy piece of orthofiber suture from the fabella to a small hole in the cranial tibia. This suture runs in the same plane as the cranial cruciate ligament and prevents abnormal motion (drawer) across the joint. This suture aims to stabilize the knee while the body forms a bridge of fibrous tissue that will hold the knee stable in the future. This process can take 8 weeks.

Complications

Cranial cruciate ligament injury leads to a cascade of events, including progressive osteoarthritis and medial meniscal tears. The instability results in synovitis (inflammation of the joint capsule), articular cartilage degeneration, periarticular osteophyte formation, and capsular fibrosis (arthritis).

Progressive osteoarthritis continues even after stabilization of the knee regardless of the procedure used for stabilization. There are no studies supporting one method over another with respect to the progression of arthritis.

The most common complications are swelling at the incision site, seroma along the incision, premature staple removal by the dog. These complications are fairly easily dealt with. If the dog removes his staples, the incision should be flushed and closed, and he should be placed on antibiotics. Swelling can be minimized by icing the incision 3 times a day. Seroma is a benign build-up of fluid in the space between the skin and the fascia. Seromas tend to be self-limiting, but if they are very big, they should be drained, and the dog should be placed in a bandage. The concern with draining them is that you can introduce bacteria into the surgical site. Most of the time, hot packing and time resolve the problem. Infection is a potential problem with any surgery. It can occur for no reason, just because of having surgery. This happens in less than 1% of the cases. Infection most often occurs secondary to licking or chewing at the incision. The use of an e-collar can minimize this. If the infection is severe, surgery may be necessary to flush the joint and obtain cultures.

The most concerning problem is implant failure and migration. Reported complications are suture failure either by elongation, failure at the fabella, or breakage. The most common reason for these types of complications is an event that traumatizes the surgical repair, overactivity, falling, running, jumping, etc. They have, however, been reported not in association with a traumatic event. These complications require revision surgeries to stabilize and repair the damage.

Meniscal tears are fairly frequent in association with cranial cruciate tears. If the meniscus is not torn, we release it from its caudal attachment. Subsequent meniscal tears occur in 6.3% of the cases.

Patellar Luxation

The patella or kneecap is a small bone buried in the tendon of the quadriceps muscles. The patella normally rides in a groove in the distal femur. The patellar tendon attaches to the tibial crest. This is a bony prominence at the top of the tibia, just below the knee. The patellar tendon, patella, and quadriceps muscles are to be in alignment with one another. Patellar luxation is when the patella is outside the groove when the knee is flexed. Patellar luxation can be characterized as medial (to the inside of the knee) or lateral (to the outside of the knee), or bi-directional (goes both medial and lateral).

Incidence

Patellar luxation has been described as the most common congenital anomaly in dogs, diagnosed in 7% of puppies. Patellar luxation affects both knees in 50% of all cases, resulting in discomfort and bilateral lameness. In most studies, small-breed dogs are 10 times more commonly affected than large dogs, especially the Boston terrier, Chihuahua, Pomeranian, miniature poodle, and Yorkshire terrier. It is now more common to see medium and large-breed dogs are experiencing medial patellar luxations. Less commonly seen luxations are lateral luxations or bi-directional luxations.

Epidemiology of patellar luxation

- Dogs with patellar luxation are born with the disease (congenital) in 82% of cases

- Both knees affected in 50% of cases

- The luxation is medial in 98% of small dogs, around 80% in medium and large-breed dogs and 67% of giant-breed dogs

- Females are 1.5 times more likely to be affected than males

Causes

Although the cause of patellar luxation remains unclear, early diagnosis of bilateral diseases in the absence of trauma and breed predisposition is suggestive of a congenital or developmental misalignment of the extensor mechanism. Possible causes include:

- Abnormal conformation of the hip joint, such as hip dysplasia

- Malformation of the femur, with angulation and torsion

- Malformation of the tibia

- Deviation of the tibial crest, the bony prominence onto which the patellar tendon attaches below the knee

- Tightness/atrophy of the quadriceps muscles, acting as a bowstring

- A patellar tendon that may be too short or too long

Signs and symptoms

Clinical signs associated with patella luxation vary greatly with the severity of the disease: this condition may be an incidental finding detected by your veterinarian on a routine physical examination or may cause your pet to carry the affected limb up all the time. Most dogs affected by this disease will suddenly carry the limp up for a few steps and may be seen shaking or extending the leg prior to regaining its full use. As the disease progresses in duration and severity, this lameness becomes more frequent and eventually becomes continuous. In young puppies with severe patella luxation, the rear legs often present a “bow-legged” appearance that worsens with growth.

When to Seek Veterinary Advice

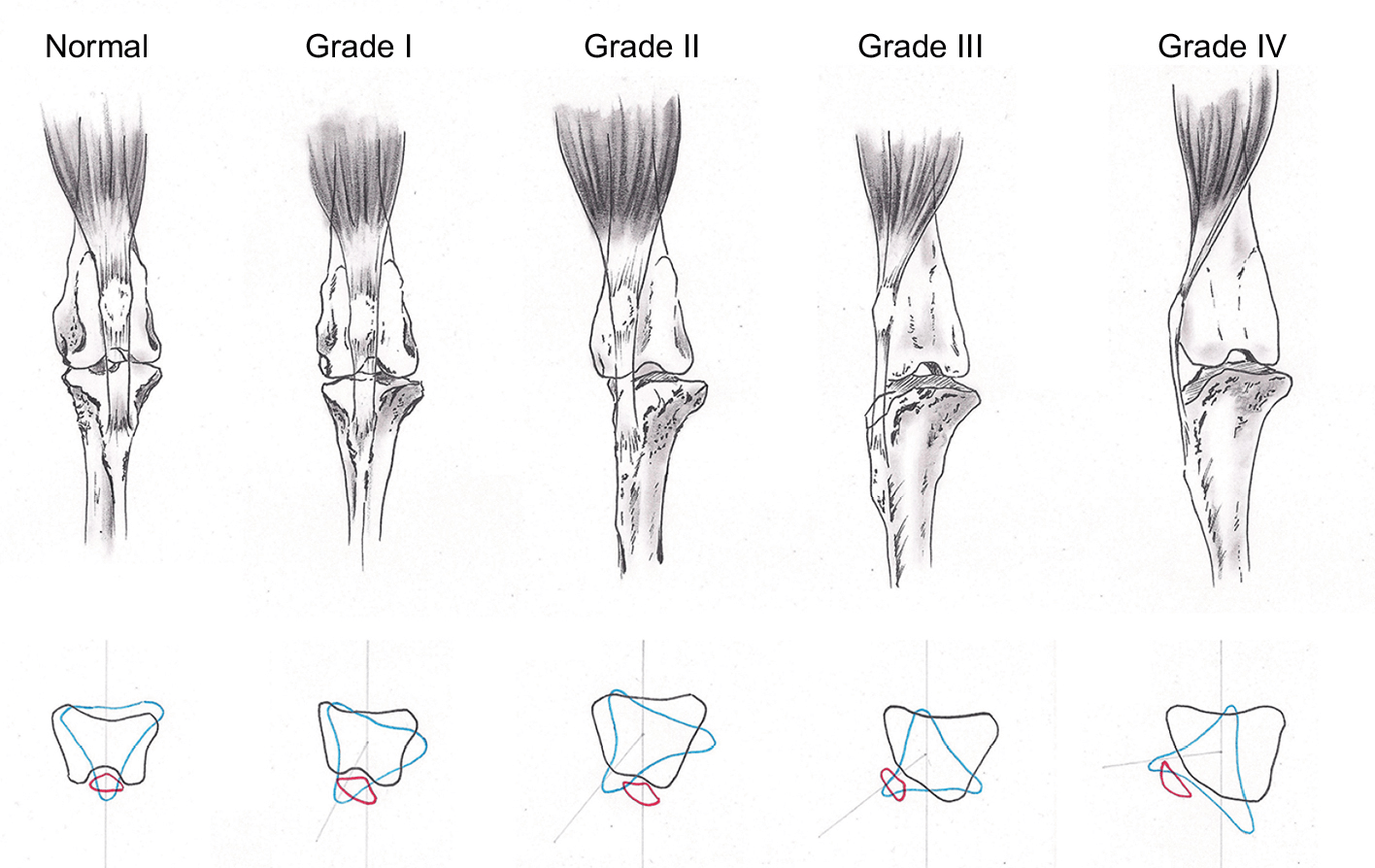

You should seek veterinary surgical advice if you have any concerns about the gait of your pet or if your primary care veterinarian advises you to do so. The severity of patella luxation has been graded on a scale of 0 to 4, based on orthopedic examination of the knee. Surgical treatment is typically considered in grades 2 and over:

- Grade 1: Can be luxated but reduces without manipulation

- Grade 2: Can be reduced by manipulation

- Grade 3: Spontaneous luxation found at least once in standing-reducible

- Grade 4: Irreducible luxation

What Will Happen If Patella Luxation is Left Untreated?

Every time the knee cap rides out of its groove, cartilage is damaged, leading to osteoarthritis and associated pain. The knee cap may ride more and more often out of its normal groove, eventually exposing areas of bone. In puppies, the abnormal alignment of the patella may also aggravate the shallowness of the femoral groove and lead to serious deformation of the leg. In all dogs, the abnormal position of the knee cap destabilizes the knee and predisposes affected dogs to rupture their cranial cruciate ligament, at which point they typically stop using the limb.

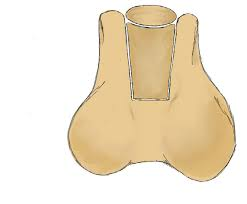

Wedge Recession

What Options are Available for Treating Patellar Luxation?

Patellar luxations that do not cause any clinical sign should be monitored but do not typically warrant surgical correction, especially in small dogs. Surgery is considered in grades 2 and over. One or several of the following strategies may be required to correct patella luxation:

- Reconstruction of soft tissues surrounding the knee cap to loosen the side toward which the patella is riding and tighten the opposite side

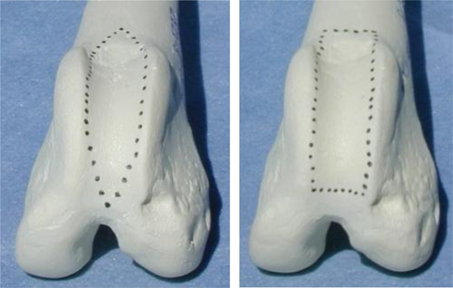

- Wedge Recession – Deepening of the femoral groove so that the kneecap can sit deeply in its normal position

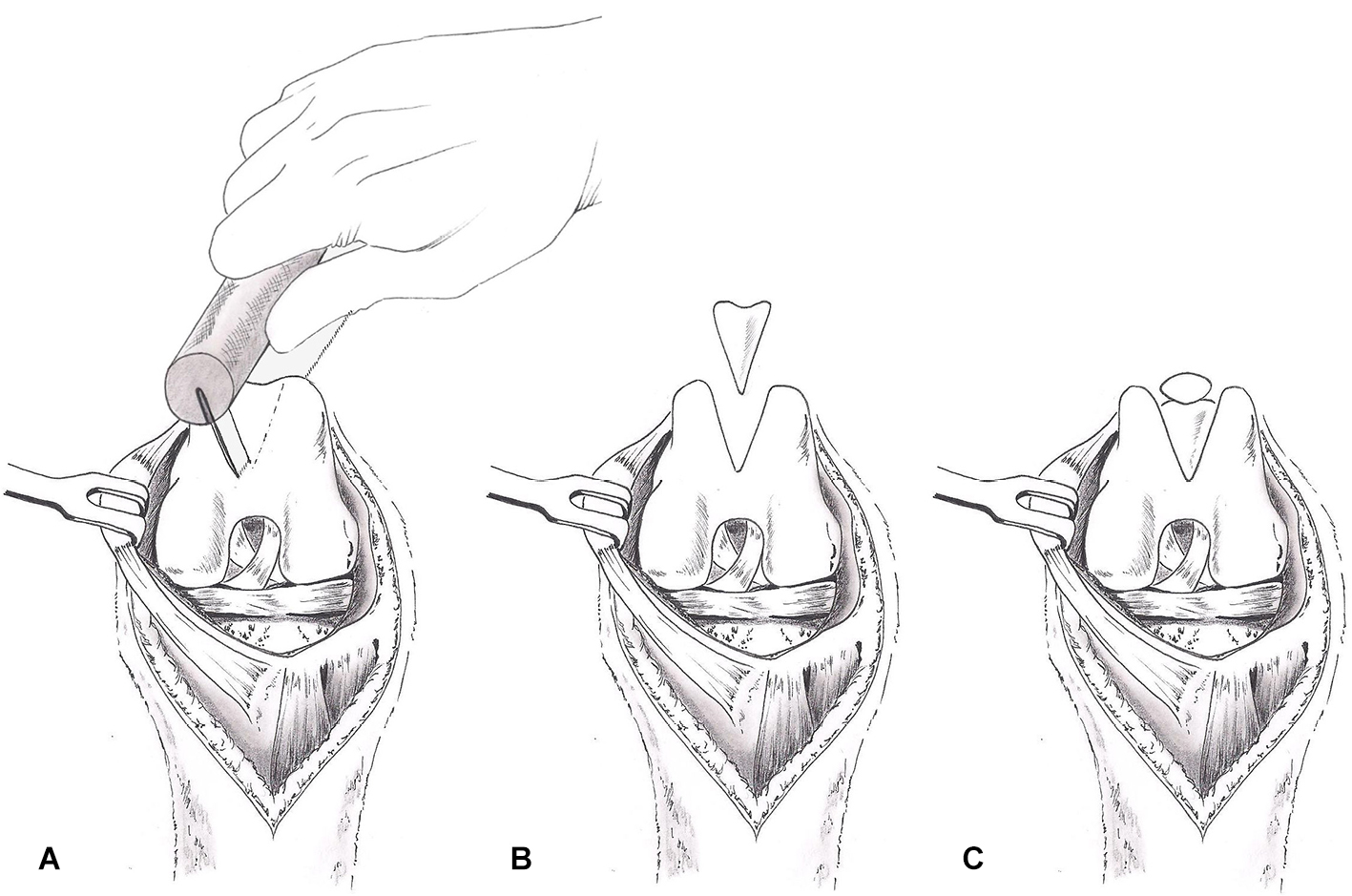

- Tibial tuberosity transposition – Transposing the tibial crest, bony prominence onto which the tendon of the patella attaches below the knee. This will help realign the quadriceps, the patella, and its tendon.

- Correction of abnormally shaped femurs is occasionally required in cases where the kneecap rides outside of its groove most or all the time. This procedure involves cutting the bone, correcting its deformation, and immobilizing it with a bone plate.

Block Recession

Prognosis

Over 90% of owners are satisfied by the progress of their dog after surgery.

Complications:

Osteoarthritis is expected to progress on radiographs. However, this does not necessarily mean that your dog will suffer or be lame as a result. Keeping your pet trim and encouraging swimming/walking rather than jumping/running will help prevent or minimize clinical signs of osteoarthritis.

Some degree of kneecap instability will persist in up to 50% of cases. This does not cause further lameness in the majority of cases. Migration or breakage of surgical implants used to maintain bones in position occurs rarely. Infection is a rare complication.

Prevention:

Because some breeds are predisposed to this condition, dogs diagnosed with patella luxation should not be bred.

MRIT, MPL Consent Form

Please fill out this form as completely and accurately as possible so we can get to know you and your pet(s) before the procedure.