Mobile Veterinary Services

We seek to build a practice that provides individualized, thoughtful, and quality care to our patients through every stage of their life.

“Bringing specialized veterinary surgical services to you!”

Jacqueline J Mair

DVM,MBA, Diplomate ACVS

SCHEDULE TODAY!

Mobile Veterinary Services

Orthopedic Surgery

Orthopedics involve conditions that affect your pet’s skeletal system and extremities, including bones, joints, muscles, tendons, and ligaments. Orthopedic injuries can affect the mood and quality of life of your pet.

You may notice a slight limp, avoidance of physical activities like jumping, hesitation to get up, or other signs that your pet is experiencing discomfort. Thankfully, there are a number of treatments available that can reduce orthopedic pain for your pet, and Mobile Surgery Services is committed to finding a treatment plan that will work best.

Orthopedic Surgery Services

- Stifle Stablization

- MRIT, Tightrope, TPLO (all size patient)

- Medial Patellar Luxations

- Femoral Head & Neck Ostectomy (FHO)

- Hip Luxation

- Fracture Repair

- Shoulder Osteochondrosis Desicans (OCD)

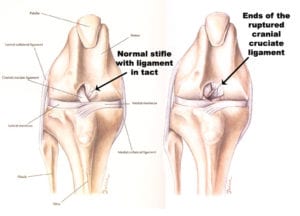

Cranial Cruciate Ligament Rupture

Cranial cruciate ligament rupture is one of the most common orthopedic injuries in the dog. The primary cause of rupture is degeneration of the ligament and rarely just trauma. Many dogs that tear one cruciate ligament will tear the other within 1 to 2 years of the first injury.

The cranial cruciate ligament is the primary stabilizer of the knee. Once it ruptures, the dog will become acutely lame due to severe inflammation that occurs within the joint. This will generally improve within the first few days if the dog is placed on anti-inflammatory medications. We believe chronic lameness is associated with instability within the stifle joint. This chronic lameness is caused by the tibial plateau angle. In the dog, the tibial plateau slopes caudally. When the dog bears weight, the femur hits the top of the tibia and slips backward down the tibial plateau. When this occurs chronically, the immobile medial meniscus can be crushed and torn.

Cranial cruciate ligament injury leads to a cascade of events, including progressive osteoarthritis and medial meniscal tears. The instability results in synovitis (inflammation of the joint capsule), articular cartilage degeneration, periarticular osteophyte formation, and capsular fibrosis (arthritis). Progressive osteoarthritis continues even after stabilization of the knee regardless of the procedure used for stabilization. There are studies to support dogs having tibial plateau leveling osteotomies will have less osteoarthritis than dogs undergoing alternative procedures. Dogs undergoing TPLO are less likely to have meniscal tears later than dogs having tibial tuberosity advancement (TTA).

The tibial plateau leveling osteotomy is chosen over the traditional extracapsular repair utilizing nylon. It is the gold standard in stifle stabilization. This procedure is primarily chosen for active dogs of all sizes. It is the procedure of choice for animals of any size for many surgeons. Extracapsular repair can be very effective in dogs especially utilizing the TightRope implant if they are not active. For clients that cannot choose the TPLO for reasons of expense, the development of the TightRope Implant gives owners a viable option.

MRIT (Modified Retinacular Imbrication Technique) or Lateral Suture

The MRIT or Lateral suture is an extracapsular repair (it takes place outside of the joint capsule). The hallmark of this procedure is the elimination of abnormal motion called drawer. The surgery has historically utilized monofilament nylon as the implant. Most surgeons no longer use nylon but chose orthofiber, which is far superior to nylon. The implant is placed from the lateral fabella to a point in the tibia. It is then tightened and knotted or crimped in a tight position to eliminate abnormal motion.

This procedure requires the formation of a fibrous tissue bridge across the joint capsule that will maintain stability of the joint over the life of the dog. The healing process takes about 8 weeks. This time is meant to allow the formation, contraction, and maturation of a fibrous tissue bridge.

The shortcomings of the procedure are in large dogs whose weight is such that they elongate the nylon or break the nylon during the healing process. The premature breakage of the nylon too early in the healing process can lead to failure and return of drawer. Elongation of the nylon can lead to the return of some degree of abnormal motion or drawer, which may or may not be tolerated in a large breed dog. Should either breakage or elongation of the implant occur, it is possible to replace the implant without much difficulty and still have a positive outcome. If there is failure, a second surgery will add expense will mean it costs as much as a tibial plateau leveling osteotomy would have in the first surgery.

This is a more economical and less invasive procedure that is appropriate for many dogs. It does not matter how you get to a positive outcome, just that you do achieve a stable and comfortable knee for your pet. A dog with Cushing’s Disease or hyperadrenocorticism would be a concern due to the overproduction of endogenous steroids, which can inhibit the formation of fibrous tissue.

TightRope Procedure:

The TightRope is a vast improvement in the implant utilized in the MRIT or Lateral Suture procedure. The TightRope implant was developed several years ago by Arthrex. The procedure does not require an osteotomy(cutting the bone) as do the TPLO or TTA procedure. This implant only requires small bone tunnels in both the distal femur and proximal tibia. The implant is placed in the best isometric position through the tunnels and secured by placing buttons against the bone, knotting one side of the implant. Your goal is to achieve a joint without drawer or instability.

The implant is a FiberTape or Kevlar like material which is much stronger than monofilament nylon. This type of implant has been utilized in human sugery for quite some time. This is a great new option for large breed dogs. The strength of the implant means they are unlikely to stretch or break the nylon. It allows owners to choose a less invasive and more economical procedure for their dog.

http://www.arthrexvetsystems.com/en/mediacenter/clientinformation/index.cfm

Tibial Plateau Leveling Osteotomy (TPLO)

Most surgeons choose the tibial plateau leveling osteotomy for all active dogs. TPLO is the gold standard of stabilization in the dog. Dogs receiving a TPLO often return to function sooner. Another reason to choose this procedure is for dogs with bilateral disease to get them walking as soon as possible. There is that choosing a TPLO over another procedure will result in less osteoarthritis over time.

The premise of the TPLO is that if you reduce cranial tibial thrust to neutral, the pain associated with cranial tibial translation will resolve.

The tibial plateau leveling osteotomy changes the biomechanics to the canine stifle (knee). Normally the knee is stabilized both passively (cruciate ligament, menisci, joint capsule) and actively (muscles & tendons). The cranial cruciate is a passive constraint to cranial tibial translation as well as internal rotation. The cranial tibial translation is tested by cranial tibial thrust test. The severity of cranial tibial thrust is related to the slope of the tibia. The premise of the TPLO is that if you reduce cranial tibial thrust to neutralize the pain associated with cranial tibial translation will resolve.

The tibial plateau leveling osteotomy requires special radiographs that allow the surgeon to measure the slope of the medial plateau. The slope angle is then converted to millimeters depending on the size of the osteotomy. The procedure incorporates the release of the meniscus and debridement of the remaining cruciate ligament. A curved saw blade is utilized to make the osteotomy. The osteotomy is then rotated a specified number of millimeters. The osteotomy is then stabilized by a bone plate. Once this is completed, cranial tibial thrust should be eliminated.

The tibial plateau leveling osteotomy takes approximately 8 weeks to heal. The osteotomy must go through the process of bone healing, just like a fracture. During the healing period, your dog should have only controlled restricted exercise. This procedure requires radiographs at the 8 week after surgery to determine if healing is sufficient to allow release back to normal activity.

Tibial Tuberosity Advancement

There is evidence to the TPLO as a superior procedure.

The hallmark of this procedure is to eliminate cranial tibial translation by placing the patellar tendon perpendicular to the shear forces in the knee. This is accomplished by performing an osteotomy of the tibial tuberosity. Once this is completed, the tuberosity is advanced or moved forward to place the tendon perpendicular to the tibial plateau. The advancement is maintained by an implant called a cage, and the osteotomy is stabilized by a plate.

The tibial tuberosity advancement requires approximately 8 weeks for healing. Ideally, radiographs should be performed at 8 weeks to assess healing. During the healing process, controlled exercise is the only allowed activity. Once healed, your pet may be released to normal activity.

There is no evidence to suggest that this procedure will result in any less osteoarthritis than the TPLO or extra-capsular repair.

In conclusion, there are 4 primary procedures available to stabilize the canine stifle. Small > 10lb, medium, and large breed dogs have better outcomes with TPLO. The Tightrope can be chosen for medium to large breed less active dogs. It is important to discuss the options with your board-certified veterinary surgeon to make the best choice possible. It does not matter how you get to a stable joint, just that we achieve that result.

Tibial Plateau Leveling Osteotomy (TPLO)

Board-certified surgeons choose the tibial plateau leveling osteotomy for all active dogs. This choice is made over concerns that active dogs damage an extra-capsular repair resulting in chronic lameness. Many also believe that dogs receiving a TPLO return to function sooner. Another reason to choose this procedure is for dogs with bilateral disease to get them walking as soon as possible. There is no evidence that choosing a TPLO over another procedure will result in less osteoarthritis.

The tibial plateau leveling osteotomy changes the biomechanics to the canine stifle (knee). Normally, the knee is stabilized both passively (cruciate ligament, menisci, joint capsule) and actively (muscles & tendons). The cranial cruciate is a passive constraint to cranial tibial translation as well as internal rotation. The cranial tibial thrust test tests the cranial tibial translation. The severity of cranial tibial thrust is related to the slope of the tibia. The premise of the TPLO is that if you reduce cranial tibial thrust to neutralize the pain associated with cranial tibial translation will resolve.

The tibial plateau leveling osteotomy requires special radiographs that allow the surgeon to measure the slope of the medial plateau. The slope angle is then converted to millimeters depending on the size of the osteotomy. The procedure incorporates the release of the meniscus and debridement of the remaining cruciate ligament. Once this is completed, a jig is placed on the medial aspect of the tibia. A curved saw blade is utilized to make the osteotomy. The osteotomy is then rotated a specified number of millimeters. A bone plate then stabilizes the osteotomy. Once this is completed, cranial tibial thrust should be eliminated.

The tibial plateau leveling osteotomy takes approximately 8 weeks to heal. The osteotomy must go through the process of bone healing, just like a fracture. During the healing period, your dog should have only controlled exercise. This procedure requires radiographs at 8 weeks after surgery to determine if healing is sufficient to allow release back to normal activity.

TightRope Cranial Cruciate Procedure

TightRope Implant:

The TightRope was developed by Arthrex Vet Systems to improve upon the extracapsular procedure used for years in veterinary medicine to stabilize the cranial cruciate deficient stifle. This technique does not require cutting of the bone as do the tibial plateau leveling osteotomy and tibial tuberosity advancement. The TightRope utilizes small bone tunnels created with a drill in both the femur and tibia. The implant is placed through these tunnels and fixed in place to eliminate abnormal motion. The implant is made of a biomaterial called FiberTapeR. FiberTapeR is a kevlar-like material used extensively in human surgery for many orthopedic applications. This material has properties that make it stronger and less prone to failure than the other suture materials(monofilament nylon) used for cranial cruciate reconstructions.

Arthritis:

All dogs with cranial cruciate deficient stifles (knees) will develop arthritis. Research has shown that dogs having a TPLO develop less arthritis than those undergoing other alternative procedures. The purpose of surgery is to restore stability to the knee that existed prior to the cranial cruciate tear. Surgical stabilization using any method is not a cure for arthritis.

Postoperative Complications:

All surgical procedures have the potential for complications associated with them. The overall complication rate for the TightRope procedure is currently 20%. There has been a 9.9% rate of major complications (4% meniscal tears; 3.1% implant/technique failures; and a 2.8% infection), which require further treatment. There has been a 10.1% minor complication rate, which has not required additional surgical or medical treatment to resolve. Click on this link to view Arthrex Data on TightRope – TightRope-CCL-MultiSite-Data-Sept-09.

How to be Successful:

The most important thing you can do after surgery is to follow your discharge instructions exactly. Come to your follow-up appointments so we can assess healing and make sure things are going well. Report any concerns immediately so we can take care of any issues as soon as possible. This is more important than what occurs in surgery. Keep your pet at its ideal weight. Overweight dogs have more difficulty with recovery and arthritis pain.

Medial Patellar Luxation (MPL)

The patella or kneecap is a small bone buried in the tendon of the quadriceps muscles. The patella normally rides in a groove in the distal femur. The patellar tendon attaches to the tibial crest. This is a bony prominence at the top of the tibia, just below the knee. The patellar tendon, patella, and quadriceps muscles are to be in alignment with one another. Patellar luxation is when the patella is outside the groove when the knee is flexed. Patellar luxation can be characterized as medial (to the inside of the knee) or lateral (to the outside of the knee), or bi-directional (goes both medial and lateral).

Incidence

Patellar luxation has been described as the most common congenital anomaly in dogs, diagnosed in 7% of puppies. Patellar luxation affects both knees in 50% of all cases, resulting in discomfort and bilateral lameness. In most studies, small-breed dogs are 10 times more commonly affected than large dogs, especially the Boston terrier, Chihuahua, Pomeranian, miniature poodle, and Yorkshire terrier. It is now more common to see medium and large breed dogs are experiencing medial patellar luxations. Less commonly seen luxations are lateral luxations or bi-directional luxations.

Epidemiology of patellar luxation

- Dogs with patellar luxation are born with the disease (congenital) in 82% of cases

- Both knees affected in 50% of cases

- The luxation is medial in 98% of small dogs, around 80% in medium, and large-breed dogs and 67% of giant-breed dogs

- Females are 1.5 times more likely to be affected than males

Causes

Although the cause of patellar luxation remains unclear, early diagnosis of bilateral diseases in the absence of trauma and breed predisposition is suggestive of a congenital or developmental misalignment of the extensor mechanism. Possible causes include:

- Abnormal conformation of the hip joint, such as hip dysplasia

- Malformation of the femur, with angulation and torsion

- Malformation of the tibia

- Deviation of the tibial crest, the bony prominence onto which the patellar tendon attaches below the knee

- Tightness/atrophy of the quadriceps muscles, acting as a bowstring

- A patellar tendon that may be too short or too long

Signs and symptoms

Clinical signs associated with patella luxation vary greatly with the severity of the disease: this condition may be an incidental finding detected by your veterinarian on a routine physical examination or may cause your pet to carry the affected limb up all the time. Most dogs affected by this disease will suddenly carry the limp up for a few steps and may be seen shaking or extending the leg prior to regaining its full use. As the disease progresses in duration and severity, this lameness becomes more frequent and eventually becomes continuous. In young puppies with severe patella luxation, the rear legs often present a “bow-legged” appearance that worsens with growth.

When to Seek Veterinary Advice

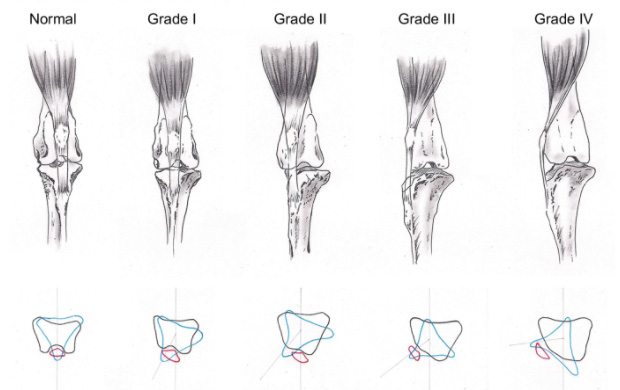

You should seek veterinary surgical advice if you have any concerns about your pet’s gait or if your primary care veterinarian advises you to do so. The severity of patella luxation has been graded on a scale of 0 to 4, based on orthopedic examination of the knee. Surgical treatment is typically considered in grades 2 and over:

-

Grade 1: Can be luxated, but reduces without manipulation

- Grade 2: Can be reduced by manipulation

- Grade 3: Spontaneous luxation found at least once in standing-reducible

- Grade 4: Irreducible luxation

What Will Happen If Patella Luxation is Left Untreated?

Every time the knee cap rides out of its groove, cartilage is damaged, leading to osteoarthritis and associated pain. The knee cap may ride more and more often out of its normal groove, eventually exposing areas of bone. In puppies, the abnormal alignment of the patella may also aggravate the shallowness of the femoral groove and lead to serious deformation of the leg. In all dogs, the abnormal position of the knee cap destabilizes the knee and predisposes affected dogs to rupture their cranial cruciate ligament. At this point, they typically stop using the limb.

What Options are Available for Treating Patellar Luxation?

Patellar luxations that do not cause any clinical sign should be monitored but do not typically warrant surgical correction, especially in small dogs. Surgery is considered in grades 2 and over. One or several of the following strategies may be required to correct patella luxation:

- Reconstruction of soft tissues surrounding the knee cap to loosen the side toward which the patella is riding and tighten the opposite side

- Wedge Recession – Deepening of the femoral groove so that the kneecap can sit deeply in its normal position

- Tibial tuberosity transposition – Transposing the tibial crest, bony prominence onto which the tendon of the patella attaches below the knee. This will help realign the quadriceps, the patella, and its tendon.

- Correction of abnormally shaped femurs is occasionally required in cases where the kneecap rides outside of its groove most or all the time. This procedure involves cutting the bone, correcting its deformation, and immobilizing it with a bone plate.

Prognosis:

Over 90% of owners are satisfied by the progress of their dog after surgery.

Complications:

Osteoarthritis is expected to progress on radiographs. However, this does not necessarily mean that your dog will suffer or be lame as a result. Keeping your pet trim and encouraging swimming/walking rather than jumping/running will help prevent or minimize clinical signs of osteoarthritis.

Some degree of kneecap instability will persist in up to 50% of cases. This does not cause further lameness in the majority of cases. Migration or breakage of surgical implants used to maintain bones in position occurs rarely. Infection is a rare complication.

Prevention:

Because some breeds are predisposed to this condition, dogs diagnosed with patella luxation should not be bred.

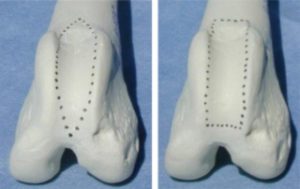

Wedge Recession:

Block Recession:

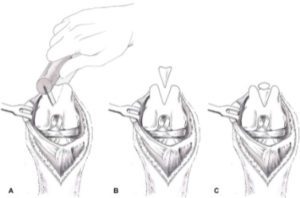

Tibial Tuberosity Transposition:

Fracture Repair

Our pets sustain fractures from primary, secondary, and major trauma such as being hit by a car, fighting with another animal, being attacked by another animal, or falling. If this happens, they will be very painful and hold up the limb that is injured. There will usually be a large amount of swelling and can be severe injuries to the skin. This type of injury requires immediate veterinary care. On rare occasions, our geriatric pet can sustain a fracture with very little or no trauma. This is caused by a cancerous process that has damaged the bone.

What should you know if your pet sustains a fracture?

All fractures are different. Each fracture must be evaluated to determine the best option for stabilization and return to function. If your pet has suffered serious trauma and has other injuries, it is important they receive emergency care to provide life-saving support and pain management until they are in a good metabolic position to have the fracture repaired.

Soft Tissue Surgery

Soft Tissue Surgery Services

- Spay/Neuter

- Prophylactic Gastropexy

- Abdominal Exploratory

- Liver Biopsy

- Mass Removal

- Brachycephalic Syndrome Surgery (Soft Palate and Nares)

- Anal Saculectomy

- Salivary Mucocele

- Perineal Urethrostomy (cat)

- Cystotomy

- Scrotal Urethrostomy Dog

- Amputation (Digit or Limb)

- Bone Biopsy

Abdominal Exploratory

There are many reasons your pet may require an abdominal exploratory. Some common reasons are:

- Ingestion of a foreign body that is causing an obstruction

- Vomiting and diarrhea that will not resolve

- Mass detected in radiographs or ultrasound

Chronic vomiting and diarrhea sometimes cannot be properly diagnosed without intestinal and gastric biopsies. An abdominal exploratory will allow biopsies of the liver, pancreas, stomach, and small intestine. This can give us a definitive diagnosis and allow appropriate therapy to ensue.

Acute vomiting can be due to an upper gastrointestinal obstruction. Our pets often eat object such as toys, beds, clothing that can cause an acute obstruction. Sometimes these obstructions can be diagnosed with x-rays or radiographs. There are times when ultrasound is necessary to confirm the problem. If foreign material is lodged in the upper gastrointestinal tract, it is important to have it removed to prevent life-threatening dehydration or peritonitis secondary to performation of the bowel.

Linear foreign bodies are some of the most serious foreign bodies we see in dogs and cats. They occur secondary to your pet eating thread or carpet that can become lodged in the stomach then travel through the intestinal tract. These cases may be diagnosed with x-rays (radiographs) and/or abdominal ultrasounds.

The intestines become plicated with the thread or linear material cutting into the mucosa. As the intestines become plicated, the blood supply is compromised and can lead to areas of necrosis or death. Once there is a perforation in the intestines, intestinal contents leak into the abdominal cavity leading to peritonitis. This can result in death. The sooner a linear foreign body is surgically removed, the less likely life-threatening complications may ensue. Their removal can require an incision into the stomach (gastrotomy) and the intestines(enterotomy). More severe plications may require multiple incisions into the intestines(enterotomies). If the intestinal tract contains areas of necrosis (death), it may be necessary to resect or remove a portion of the small intestine. The vast majority of these cases have an excellent outcome, but there are severe cases that may suffer complications. Acting on these cases in a timely fashion is very important.

Abdominal masses are most likely associated with one of the following structures:

- Liver

- Spleen

- Stomach

- Intestinal Tract

Abdominal masses can be often be diagnosed with x-ray and ultrasound examination. There are rare occasions when the masses cannot be associated with a specific organ because of their size, or it is a sarcoma not associated with an organ.

Liver masses are best dealt with in a 24 hours facility. These are complicated surgeries with potential complications that can occur and require close supervision.

Gastric Dilitation & Volvulus (GDV)

What is a GDV or gastric dilatation & Volvulus?

This emergency illness tends to occur in large breed dogs. When it occurs, it can be associated with a mortality rate as high as 45%. This event is caused by enlargement of the stomach with rotation of the stomach, causing an obstruction. When the stomach becomes twisted, it prevents fluid or gas from leaving the esophagus or entering the small intestines. This causes the stomach to continue to get bigger. The combination of twisting and filling with fluid and gas damages the blood supply to the stomach.

Why does it happen?

The cause of GDV is unknown. It does, however, seem that exercise after ingestion of a meal or water can contribute to the occurrence of a GDV.

What can be done to prevent GDV?

The best way to prevent a GDV is to have a procedure called prophylactic gastropexy. This can be done when your female dog is spayed. It does require a slightly longer abdominal incision, but this is the ideal time. If you have a large breed male dog, a gastropexy can be done when he is neutered.

How do you know if your dog has a GDV or is bloated?

Common Clinical Signs of Bloat or GDV:

- Unproductive retching

- Does your dog seem like they are vomiting but only bringing up saliva

- Are they collapsed, pale and weak

- Does their abdomen seem very bloated or distended

What’s the next step?

Gastric dilatation and volvulus is a surgical emergency. You must see your veterinarian immediately. If this occurs after hours you cannot wait to go to the nearest emergency clinic. I am available in Milford at Veterinary Care Specialists upon request.

Treatment:

- Stabilization is very important. This requires an iv catheter, iv fluids, pain medications, physical examination.

- Bloodwork is very important. If you can obtain a lactate, this can be a good measure of perfusion and give you a clue to how severely your patient is affected by shock.

- Once stabilized, a right lateral radiograph should be obtained to confirm the diagnosis.

- If the patient is greater than 7 or 8 years of age, I would also recommend getting chest radiographs to rule out any other disease process. GDVs can occur secondary to other disease processes on occasion.

- Once the patient is stabilized, the stomach should be decompressed via trocarization or stomach tube. Ideally, this should be done prior to transfer or surgery.

- Surgery is a necessity. This problem will not resolve. The longer it goes without definitive treatment, the more severely the dog is affected by shock, gastric necrosis is possible, and splenic damage.

- A gastropexy needs to be performed in the stable patient. It is possible that if gastric necrosis has occurred that a portion of the stomach may require removal. The spleen must be evaluated to determine if it is viable. If thrombosis has occurred, it must be removed.

How can I help?

If I am available, I can perform the surgery in your office if you feel you can manage aftercare within your facility. I am also always available at Veterinary Care Specialists in Milford. I am available after hours if the owner wants to have a board-certified surgeon perform the surgery. The on-call doctor will call me in to take care of your clients.

Splenectomy

The spleen has several functions: blood storage, blood filtration, and processing of particles such as bacteria, parasites, damaged or old red blood cells. It contributes to the immune defenses, plays a role in hematopoiesis and iron metabolism. Both dogs and cats can live very normal lives without their spleens. The spleens contribution to the immune system and hematopoiesis is small in the adult animal.

There are many reasons a dog may require a splenectomy, but there are two very common reasons. The first is a benign splenic nodule or mass called a hematoma. This may be found in routine geriatric screening radiographs or, more likely, an ultrasound. It is possible the mass is so large it has caused anemia or can be found on abdominal palpation. The other common reason is due to acute blood loss secondary to rupture of a hematoma or hemangiosarcoma. In this case, splenectomy is required to stop life-threatening bleeding or hemorrhage. The only way to diagnose the kind of mass is with a histopathological review of the tissue once it is removed. There are screening tests that should be done to rule out metastatic disease to the best of our ability. They are chest radiographs and abdominal ultrasounds. It is important to know that disease at the cellular level cannot be seen on radiographs, and liver nodules do not always appear to be a result of malignancy. While screening tests are important and do help, they are not perfect, and there is always a chance the surgeon can find more advanced diseases than anticipated.

It may be the case that dogs with acute blood loss require hospitalization and the care of a 24-hour facility.

If you have a non-emergent case that can be supervised in your office, I would love to help you with this case.

Mass Removal

Some skin masses are benign and easily removed without the necessity for large surgical margins. If you have a client and patient with a mass that concerns you, it requires large surgical margins. I would love to help!

A large list of soft tissue masses can be resolved in the first surgery if large surgical margins 2-3 cm are taken. Some examples of these are mast cell tumors grade I & II; hemangiopericytomas; soft tissue sarcomas, melanomas, squamous cell carcinomas, mammary adenocarcinomas. Surgical margins include the tissue next to the tumor as well as deep or underneath the tumor. This may seem difficult to achieve, but in many cases can be achieved with the help of skin flaps. Once the mass has been incompletely excised, a successful second surgery can be difficult or impossible as it would be necessary to remove the entire scar with margins.

I would love to be available for consultations prior to surgery or perform the surgery for you at your hospital.